Hello

Congrats to all of you for surviving 3 terms at ISB. As the crossover term begins, not sitting with your own section feels a bit weird, doesn’t it? I don’t get the same Jedi vibe in electives.

Anyway, while doing the case comp I (like a lot of you) came across the one and only successful application of ONDC – Namma Yatri. It is a ride sharing app for autos in Bangalore. It might look like Uber and Ola, but it works very differently. It is a decentralized platform i.e., it does not involve a third-party market maker like Uber and Ola do. I remember when it was launched in Bangalore, every time I went to the office a new auto driver would tell me how I should only book rides using Namma Yatri. They don’t know that if you live in Bangalore you need to develop the skill of booking cabs on 5 different apps at the same time.

Today’s edition is about decentralization, especially in the ride sharing market and how it might create more problems than solutions.

Let’s start with some basics. Ride-sharing market is a two-sided marketplace where there is a demand from riders and supply from drivers. Most of the time demand is higher than supply and the companies need to pay a game of balance. If the price is too high, riders will not pay. If the price is too low, the drivers will refuse to drive.

How do you find the right price? That’s where the pricing model comes in. Uber and Namma Yatri use very different pricing models to solve this problem and the model has deep implication on what the outcomes are.

To understand these implications, I went to our in-house economics expert Professor Shiv Dixit. I'm sure he felt like he was explaining black holes to a dog, but I think after the first 10 minutes I started to understand a little bit.

Price Floors

Let’s start with a scenario in which every rider who wants a cab is shown the same price. In this case, we will assign the cabs randomly and this will increase the wait time for everyone. The problem is that many of the riders value this ride more than others, i.e., they would be willing to pay more than the price shown.

A good way to solve this would be to just increase the price shown on the app. This will lead to two outcomes. People who value the ride more will accept the price and continue looking for a cab. More interestingly, new drivers will enter the market. These are drivers who were not willing to drive at the lower price. Once the price goes up, they are ready to go.

As new drivers enter the market supply increases and the price goes down again.

This is called a price floor. Minimum price that needs to be set to match demand and supply. This is quite efficient too. People who value the ride more got it first at a higher price while people who value it less got it at a lower price.

Most cab companies use this mechanism. But not Namma Yatri. They use something called auctions.

Auctions

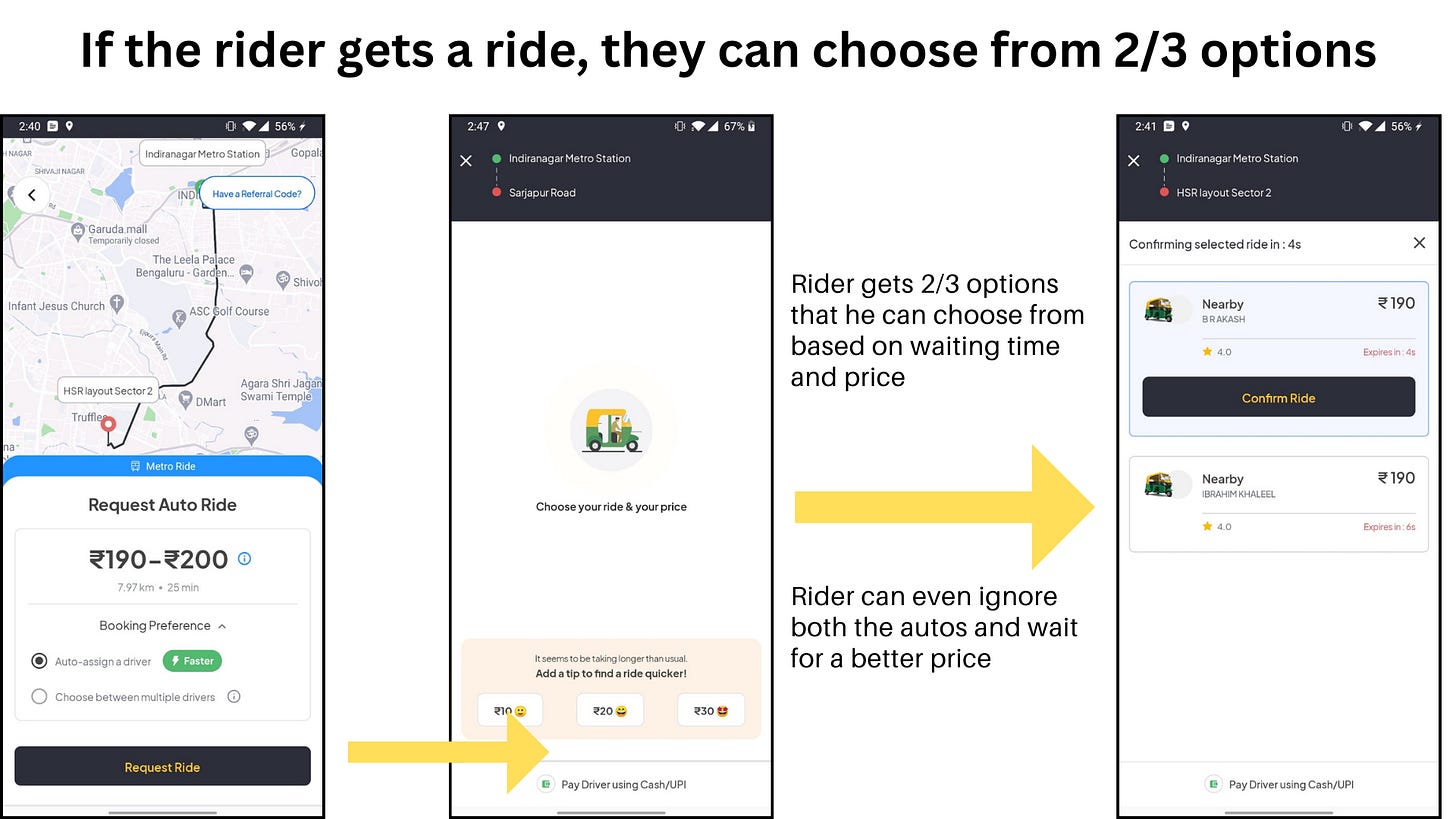

Let’s look at the demand side first. This is what happens on a busy day on the Namma Yatri app.

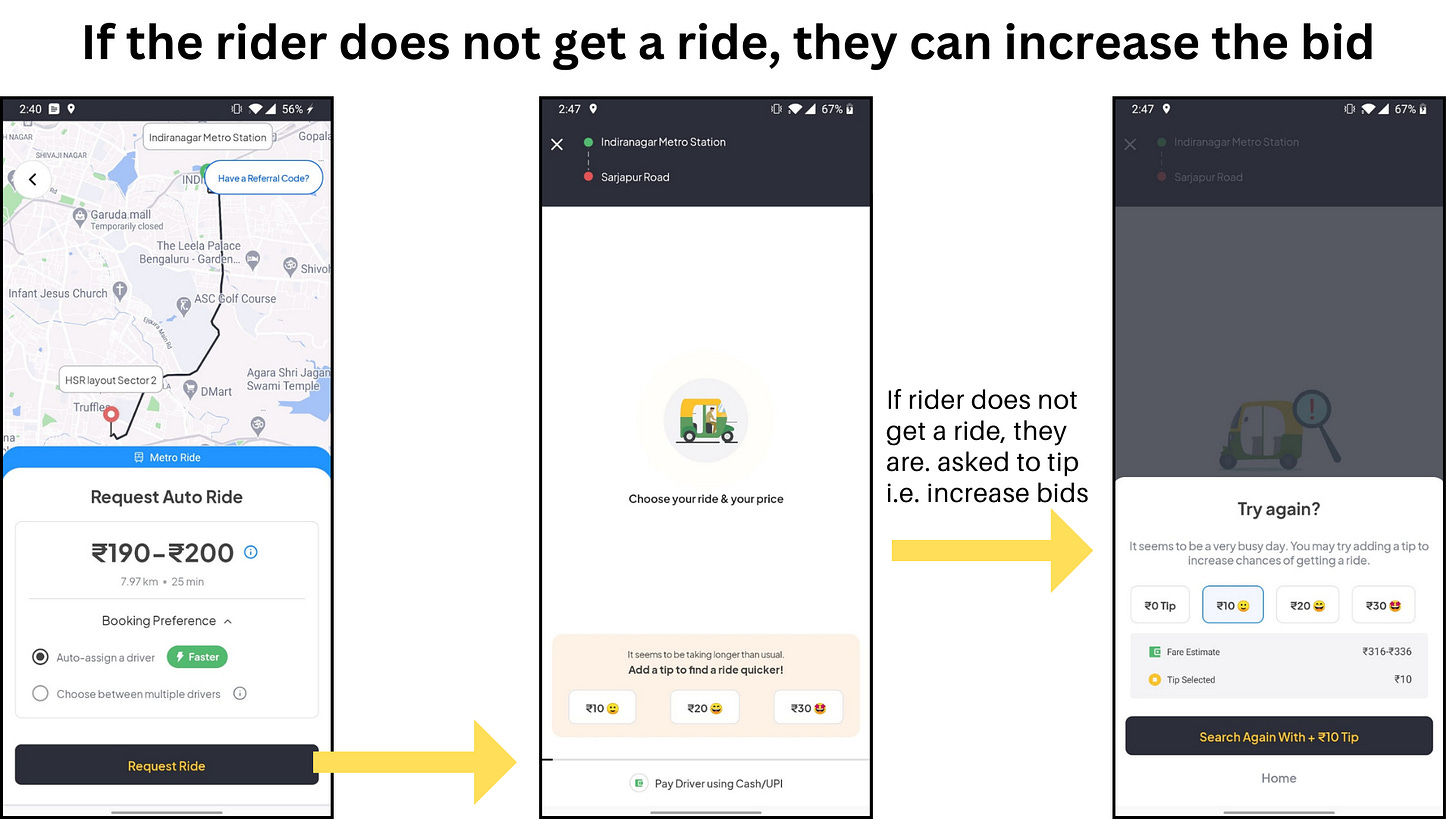

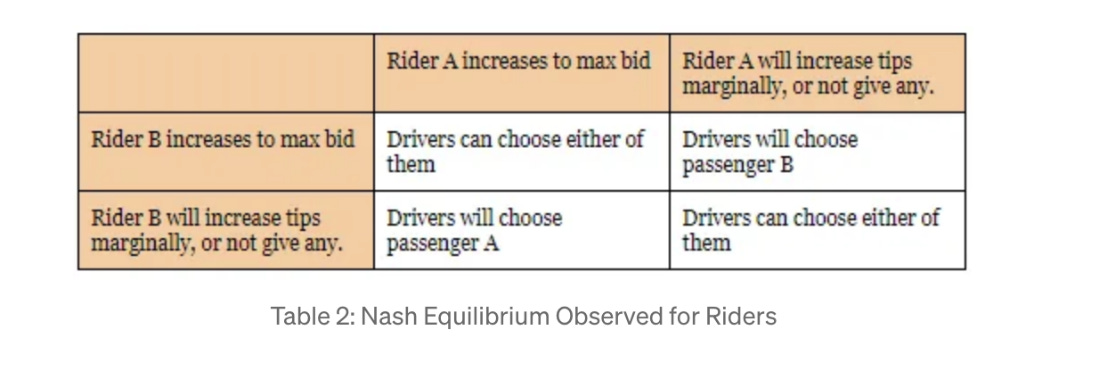

Do you notice the tips? The app says that if I increase the price (that I’m willing to pay) there is a higher probability of me getting a ride. What should I do? Well, I am doing an MBA so I should make a 2*2 matrix, figure out what other riders will do and choose the scenario with best possible outcome.

This is called a sealed bid auction where I have no idea what the other riders will “bid”. The Nash equilibrium for these drivers will be to increase the bids incrementally and that’s what we actually observe when people use it.

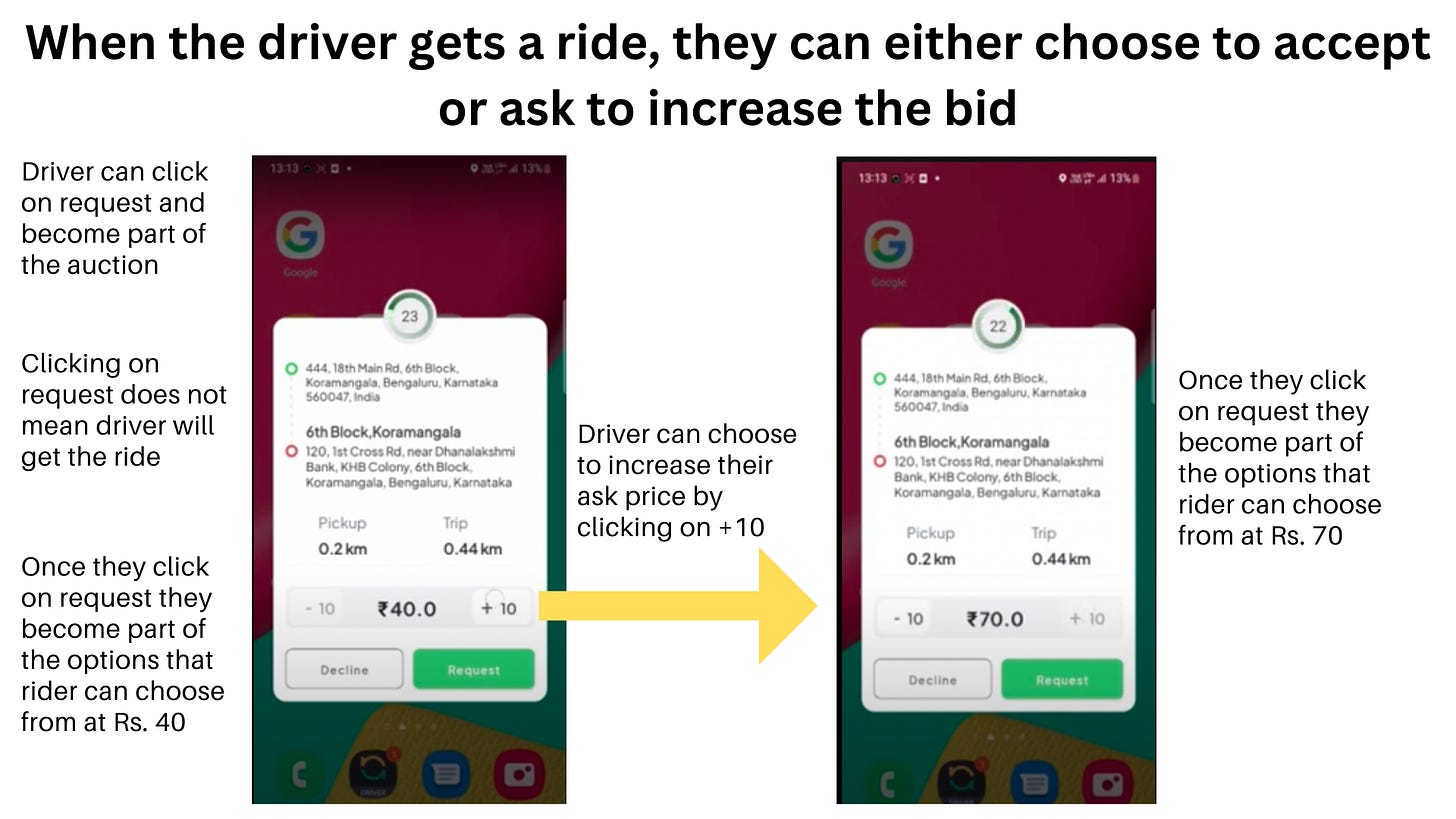

Now, let’s see the supply side. Here is what the driver sees when someone asks for a ride.

The drivers participate in an “open auction”. In this case the driver got a gig for 40Rs. He can either accept this ride or increase his ask price to a max of 70Rs, a 30Rs increase (notice that this is also the maximum “tip” that a rider can give).

Final outcome same as Uber? Or not?

If you think about it, even in the auction-based pricing world, the outcome will probably be the same. Assuming there is enough liquidity in the market (enough number of riders and drivers), riders who value the ride at 70 will increase their bid by tipping and get the ride first. When they increase the price, more auto drivers will enter the market which will reduce the price for everyone, same as before.

But there is a very big problem with this model. In an ideal market both the network forces (driver and rider) have equal power. But in this case, the riders have too much power. They can pick and choose which ride they want to take based on waiting time, price etc. On the other hand, drivers have no idea what the current demand situation is.

Looking back at the example, if they don’t accept the 40Rs ride, and the demand is not high they will lose this ride resulting in a sunk cost of 40Rs. On the other hand, if the demand is high and the driver accepts the ride then they will lose out on an opportunity cost of 30Rs.

Drivers will eventually understand this. This will create an incentive for them to form a coalition and not accept rides at all which will create artificial scarcity.

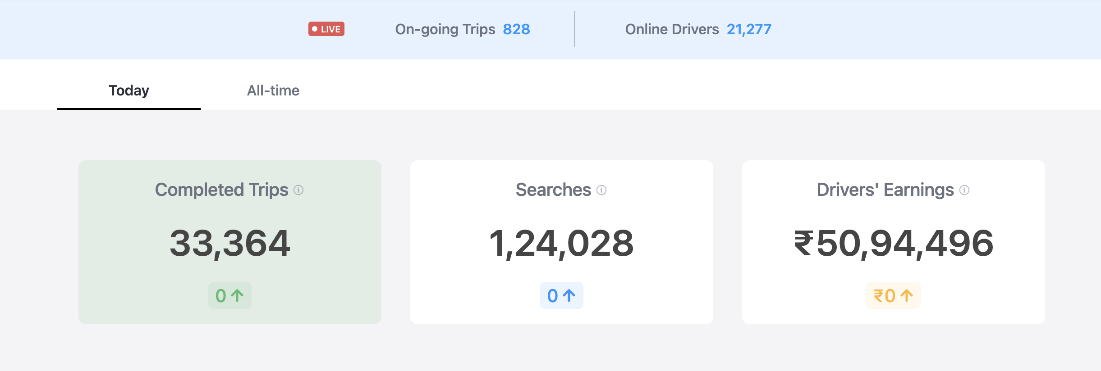

This is not just a theoretical concept. A Chinese ride-sharing giant Didi Dache followed the same auction-based model and ended up getting banned by the government. Even Namma Yatri is struggling to scale. Here is a screenshot from their website -

A 25% conversion rate is just not good enough.

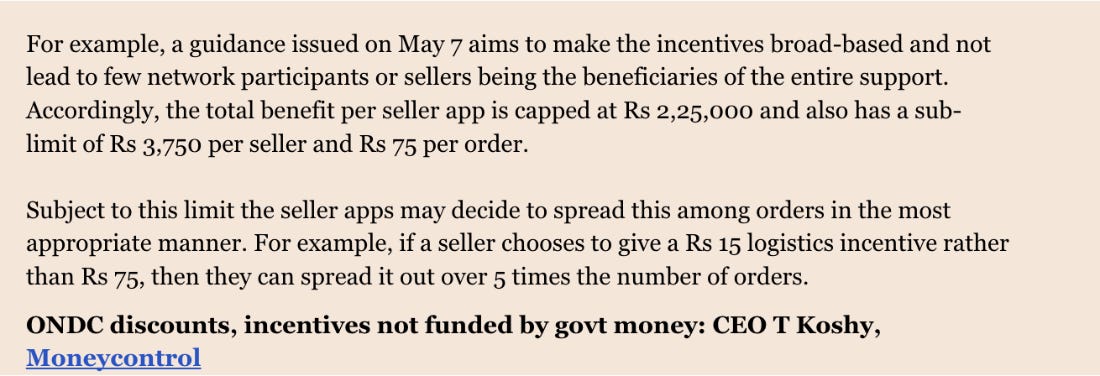

ONDC obviously understands this, and they are trying to cap the incentives.

The same situation might and probably will play out in the food-delivery market, grocery market or in any other market where one of demand or supply is significantly larger than the other.

How will the government solve it? Do they even want to solve it?

Time will tell.

Thanks

Aditya

PS: Thanks to Prof Shiv for entertaining my doubts. I know he disagrees with some of the stuff I have written but I have learnt a lot in the process of writing this.

Source: A lot of this edition is from India’s best newsletter The Nutgraf, Jensen Loke’s medium blog and the ONDC website.